The horn slit him clean across the abdomen and he watched the bull out of the pass and back to the querencia. The crowd was silent. The bull turned and was watching him, and he felt the weakness in his legs and the strange spilling out of his contents. He caught the intestines as they fell out and holding them back, still holding the muleta and the sword, he staggered towards the mayor’s box. Offal, he thought, fucking offal and at a time such as this. The mayor was standing. He looked up and tried to speak, “Dear mayor, as you see it is no use, no use at all that I continue.” He dropped the intestines into the sand as he fell forward.

The horn slit him clean across the abdomen and he watched the bull out of the pass and back to the querencia. The crowd was silent. The bull turned and was watching him, and he felt the weakness in his legs and the strange spilling out of his contents. He caught the intestines as they fell out and holding them back, still holding the muleta and the sword, he staggered towards the mayor’s box. Offal, he thought, fucking offal and at a time such as this. The mayor was standing. He looked up and tried to speak, “Dear mayor, as you see it is no use, no use at all that I continue.” He dropped the intestines into the sand as he fell forward.1.29.2010

Friday Night at 11th and Ogden

The horn slit him clean across the abdomen and he watched the bull out of the pass and back to the querencia. The crowd was silent. The bull turned and was watching him, and he felt the weakness in his legs and the strange spilling out of his contents. He caught the intestines as they fell out and holding them back, still holding the muleta and the sword, he staggered towards the mayor’s box. Offal, he thought, fucking offal and at a time such as this. The mayor was standing. He looked up and tried to speak, “Dear mayor, as you see it is no use, no use at all that I continue.” He dropped the intestines into the sand as he fell forward.

The horn slit him clean across the abdomen and he watched the bull out of the pass and back to the querencia. The crowd was silent. The bull turned and was watching him, and he felt the weakness in his legs and the strange spilling out of his contents. He caught the intestines as they fell out and holding them back, still holding the muleta and the sword, he staggered towards the mayor’s box. Offal, he thought, fucking offal and at a time such as this. The mayor was standing. He looked up and tried to speak, “Dear mayor, as you see it is no use, no use at all that I continue.” He dropped the intestines into the sand as he fell forward.1.28.2010

An Afternoon In Tunisia

The tourists had stopped where three cobblestone streets came together. The young man held out a yellow tourist carte. They had been in the souk and then they were out of it. Where the souk was shaded and jammed noisy with sellers and stalls spilling out into the little streets; the stalls packed with leather goods and painted pottery from Nabuel, Berber jewelry, chica water pipes and beaten brass plates; the sellers trying in every language to get your attention, often getting you by the arm and only three or four non mercis would get them off; it was quiet now and empty in the bright whitewashed narrows of the medina.

“Don’t be so stubborn,” the young man was saying to her. “You don’t prove anything that way.” She wore a dress and a little black top that showed much of her chest and back and arms. She stood apart from the young man.

“Anglais?” the Arab spoke to the tourists. They hadn’t seen him come up from behind. The Arab was short and dark with thick moustaches.

“Americains,” the girl said to the Arab.

The young man looked at her. She knew he did not like people to know they were Americans.

“You are lost,” said the little Arab, continuing in French. “Come with me. I know the way. The musée is just here. You do not worry.”

The Arab spoke towards the young man but kept looking at the American girl. He produced three keys from his pocket. “You see, I work at the musée,” he smiled. “Come I will show you the musée. It is the most beautiful musée in Tunis. Come.” The Arab guided the girl gently on her back in the direction.

The young man folded the map and hurried up. “He knows the way out of here?”

“Yes,” the girl said.

“From where do you come in Amerique, madame?” the Arab asked politely.

“From Philadelphie,” the madame answered.

“Ah, Philadelphie, a beautiful city,” said the Arab.

The young man said something in English and dropped back behind them.

The Arab led the American couple through a dirtier part of the medina. The buildings were faded and gray, the whitewash stripped away, with garbage strewn along streets. The garbage stunk in the sun and heat and cats searched through the piles. Some of the doorways were open and inside were men weaving on large wooden looms. In another doorway men were sawing and measuring as young boys hammered. The weavers and carpenters stopped to watch them. One of the boys yelled out something in Arabic and grinned.

“And how do you call yourself, madame?” the Arab turned to the girl.

“Elizabeth,” she said.

He looked back questioningly at the young man. “Does he not speak French?”

“He cannot.”

“Tant pis. It is too bad.” It was as though a great plan had been suddenly reduced.

“But he will enjoy the musée anyway,” he assured her, brightening, and smiled to show teeth browned by tea and nicotine. “There is much beauty inside, madame. We are close. It is just ahead.” He liked the American madame. He liked that she walked with him and the young husband walked behind. He had not known Americans before.

The Arab stopped before the heavy blue-painted doors of the Musée Dar Ben Abdallah. He waited for two women in white sifsaris to pass before taking out his keys and unlocking the doors. The Arab guided the American couple into the dark corridor and carefully shut the doors behind them.

The young man said to the girl, “You know he’ll want us to pay him.”

“I want to see the museum.”

“If that’s what you really want.”

“That’s what I want.” She did not look at him.

The Arab frowned. All the talking in English made him nervous. “The musée is closed the Monday, madame,” he said. “You were fortunate to discover me. It is beautiful.” He was worried he might lose them so close. “Venez, come. Follow me, come, madame.”

He showed the American couple out into a mosaic tiled courtyard with a stone fountain at the center. He smiled to the American girl. “It is beautiful, no? Come.” There were four doors for the four rooms of the museum, one on each wall of the courtyard. He would get the tour underway.

This first room, he explained, was consecrated to man and contains the costumes and sabers of the 18th century. He pointed out the red chechia hats in the glass case and he explained the hammam that had been reconstructed in the corner. He made the explanations like the museum guides. But he saw that the young man was disinterested. He did not understand French.

“M’sieur, here, your hands like this,” he gestured to the young man.

The Arab took the young man’s hands and rubbed the backs and then the centers of the palms with his thumbs. The Arab’s hands were coarse and dirty and his thumbnails were unusually thick. Then he kneaded the center of the young man’s forehead with his thumbs.

“He has been walking long today. He is tired. Explain this to him,” he told the American girl.

The young man nodded that he understood.

“Here madame, for you too, but different. Come, relax,” he said to her. “Do not be nervous.”

The Arab bent down and tapped three times on her knee caps. Then he felt behind her knees. He pulled at her calves and then massaged them lightly. He held her hands and pulled each of the fingers until they popped. He put his hands on her forearms and gently twisted, then pulled her arms holding her at the shoulder until the joint cracked.

“Cava mieux? You feel better? Yes, of course I make you feel better. Come, you will like the next room very much, madame.” He led them back through the courtyard and into the second room.

This room, the salle of women, is where they prepare themselves in perfume and make-up for the men. These are the hedeyed bracelets, see the engraving and they are made in gold and silver. The khalkal, to be worn by the bride around the ankle as the symbol of fidelity.

“When were you married?” the Arab asked.

“We are not married,” said the American girl.

“Not married?” It surprised him.

“No, not ever,” she said. “Seulement amis. Friends.”

“Amis,” repeated the Arab. “Ah, friends, you are friends” he grinned. He winked to the young man. He understood now. He knew what it was about. To have been so lucky. “Come, come,” he said to them.

The third room was for the preparation of the bride. There was a long red couch and walls painted in gold and a crystal chandelier. He had the young man stop at the door. He seated the American girl on the couch before an opened book, placing her hands on the pages. It is the Koran, he explained. It is for marriage and the bride is to sit as you sit.

“Come now to me, mademoiselle, vas-z toi,” the Arab said to the girl from America.

The mademoiselle stood before him. She was too far away. The Arab came close to her. “Here, here and also here,” he said, touching a point on her chin and two others on her cheeks. “A mark of beauty is made in these three places to signify the bride.”

The Arab laughed. “You are a perfect bride, mademoiselle.”

He grabbed the mademoiselle around the waist and pulled her against him. He could hold her with one arm. He glanced toward the young man at the door. The young man looked away. It was okay. He pushed his face toward hers, trying to get her lips, but she pulled away and he could only kiss her on the cheek. These girls of America. He tried again to kiss her and could again only get her cheek. He let her go and laughed. He was delighted. It was all okay.

“Come,” the Arab said to them. “We go now to the last of the rooms.”

He explained the last room was for the baby. He showed the baby items and explained their use. The mademoiselle stood with the young man just inside the door. He motioned her to come forward.

“Here, mademoiselle, come put your hands on your knees like this.”

She shook her head. She did not want to do it.

“Come, mademoiselle, do as I say. It is the heat, you are overheated,” he explained.

She glanced at the young man and stepped into the center of the room. The American girl bent over with her hands on her knees. The Arab grinned at the young man. They had a complicity developing. He pushed her black top up on her back to expose as much skin from the shoulders to her waist. She pulled up. “Stay, stay, do not move,” he told her. “Stay, mademoiselle.” He placed his hands onto the tanned, smooth skin and felt her down slowly to the little hairs on her lower back. She tensed under his touch. He turned to wink at the young man but the young man had looked away.

“It is a great relief to touch here and here,” he said running his hands along her dress to the soft flesh at her hips.

“Now stand up.”

The Arab motioned for the young man to come and stand behind her. He had the young man hold the girl’s hands behind her. The Arab stood in front of the girl and jerked up the black top to expose her stomach. The mademoiselle reacted. Her top was half off.

“Sshh, very quiet, mademoiselle. Do not move. Hold her tight, m’sieur.” His hand smoothed slowly across her stomach, then ran up between her breasts. The girl shrieked and broke free from the hold of the young man.

“No, no, not finished mademoiselle. Not finished.” He clapped her stomach with his cupped hand three times and put his ear at her belly, listening.

“Try m’sieur, try to listen,” he motioned to the young man.

The monsieur hesitated, then came around and listened.

“You hear, of course, don’t you? You hear the air?”

The young man didn’t say anything.

“Tour stop,” the Arab said to him in English. He led the Americans out through the courtyard and to the doors. The Arab stood in the darkened corridor, smiling.

“Some dinar for your tour,” he said in English.

The young man put two dinar pieces in his hand. It was half of what he expected.

“M’sieur,” he said. “Mademoiselle,” he turned to her. “Four dinar. Four dinar is raisonable.”

She did not answer and would not look at him. The young man looked serious now, even angry. It was some joke maybe.

He held out his hand again for the monsieur and smiled. The young man put a two dinar coin in his hand and said something in English. The Arab opened one of the wooden doors and looking both ways led the American tourists out onto the bright street. The Arab locked the doors and went away quickly. The little Arab was gone.

The young man unfolded the yellow tourist map and looked around.

“Are you hungry, Liz?” he said finally.

She shook her head.

“What about a mint tea?”

“I want to go back to the hotel,” she told him. “I want chocolate,” she told him. “I want chocolate and I want a shower.”

“Well,” said the young man looking at their map, “We’ll need to find out where we are first.”

“Don’t be so stubborn,” the young man was saying to her. “You don’t prove anything that way.” She wore a dress and a little black top that showed much of her chest and back and arms. She stood apart from the young man.

“Anglais?” the Arab spoke to the tourists. They hadn’t seen him come up from behind. The Arab was short and dark with thick moustaches.

“Americains,” the girl said to the Arab.

The young man looked at her. She knew he did not like people to know they were Americans.

“You are lost,” said the little Arab, continuing in French. “Come with me. I know the way. The musée is just here. You do not worry.”

The Arab spoke towards the young man but kept looking at the American girl. He produced three keys from his pocket. “You see, I work at the musée,” he smiled. “Come I will show you the musée. It is the most beautiful musée in Tunis. Come.” The Arab guided the girl gently on her back in the direction.

The young man folded the map and hurried up. “He knows the way out of here?”

“Yes,” the girl said.

“From where do you come in Amerique, madame?” the Arab asked politely.

“From Philadelphie,” the madame answered.

“Ah, Philadelphie, a beautiful city,” said the Arab.

The young man said something in English and dropped back behind them.

The Arab led the American couple through a dirtier part of the medina. The buildings were faded and gray, the whitewash stripped away, with garbage strewn along streets. The garbage stunk in the sun and heat and cats searched through the piles. Some of the doorways were open and inside were men weaving on large wooden looms. In another doorway men were sawing and measuring as young boys hammered. The weavers and carpenters stopped to watch them. One of the boys yelled out something in Arabic and grinned.

“And how do you call yourself, madame?” the Arab turned to the girl.

“Elizabeth,” she said.

He looked back questioningly at the young man. “Does he not speak French?”

“He cannot.”

“Tant pis. It is too bad.” It was as though a great plan had been suddenly reduced.

“But he will enjoy the musée anyway,” he assured her, brightening, and smiled to show teeth browned by tea and nicotine. “There is much beauty inside, madame. We are close. It is just ahead.” He liked the American madame. He liked that she walked with him and the young husband walked behind. He had not known Americans before.

The Arab stopped before the heavy blue-painted doors of the Musée Dar Ben Abdallah. He waited for two women in white sifsaris to pass before taking out his keys and unlocking the doors. The Arab guided the American couple into the dark corridor and carefully shut the doors behind them.

The young man said to the girl, “You know he’ll want us to pay him.”

“I want to see the museum.”

“If that’s what you really want.”

“That’s what I want.” She did not look at him.

The Arab frowned. All the talking in English made him nervous. “The musée is closed the Monday, madame,” he said. “You were fortunate to discover me. It is beautiful.” He was worried he might lose them so close. “Venez, come. Follow me, come, madame.”

He showed the American couple out into a mosaic tiled courtyard with a stone fountain at the center. He smiled to the American girl. “It is beautiful, no? Come.” There were four doors for the four rooms of the museum, one on each wall of the courtyard. He would get the tour underway.

This first room, he explained, was consecrated to man and contains the costumes and sabers of the 18th century. He pointed out the red chechia hats in the glass case and he explained the hammam that had been reconstructed in the corner. He made the explanations like the museum guides. But he saw that the young man was disinterested. He did not understand French.

“M’sieur, here, your hands like this,” he gestured to the young man.

The Arab took the young man’s hands and rubbed the backs and then the centers of the palms with his thumbs. The Arab’s hands were coarse and dirty and his thumbnails were unusually thick. Then he kneaded the center of the young man’s forehead with his thumbs.

“He has been walking long today. He is tired. Explain this to him,” he told the American girl.

The young man nodded that he understood.

“Here madame, for you too, but different. Come, relax,” he said to her. “Do not be nervous.”

The Arab bent down and tapped three times on her knee caps. Then he felt behind her knees. He pulled at her calves and then massaged them lightly. He held her hands and pulled each of the fingers until they popped. He put his hands on her forearms and gently twisted, then pulled her arms holding her at the shoulder until the joint cracked.

“Cava mieux? You feel better? Yes, of course I make you feel better. Come, you will like the next room very much, madame.” He led them back through the courtyard and into the second room.

This room, the salle of women, is where they prepare themselves in perfume and make-up for the men. These are the hedeyed bracelets, see the engraving and they are made in gold and silver. The khalkal, to be worn by the bride around the ankle as the symbol of fidelity.

“When were you married?” the Arab asked.

“We are not married,” said the American girl.

“Not married?” It surprised him.

“No, not ever,” she said. “Seulement amis. Friends.”

“Amis,” repeated the Arab. “Ah, friends, you are friends” he grinned. He winked to the young man. He understood now. He knew what it was about. To have been so lucky. “Come, come,” he said to them.

The third room was for the preparation of the bride. There was a long red couch and walls painted in gold and a crystal chandelier. He had the young man stop at the door. He seated the American girl on the couch before an opened book, placing her hands on the pages. It is the Koran, he explained. It is for marriage and the bride is to sit as you sit.

“Come now to me, mademoiselle, vas-z toi,” the Arab said to the girl from America.

The mademoiselle stood before him. She was too far away. The Arab came close to her. “Here, here and also here,” he said, touching a point on her chin and two others on her cheeks. “A mark of beauty is made in these three places to signify the bride.”

The Arab laughed. “You are a perfect bride, mademoiselle.”

He grabbed the mademoiselle around the waist and pulled her against him. He could hold her with one arm. He glanced toward the young man at the door. The young man looked away. It was okay. He pushed his face toward hers, trying to get her lips, but she pulled away and he could only kiss her on the cheek. These girls of America. He tried again to kiss her and could again only get her cheek. He let her go and laughed. He was delighted. It was all okay.

“Come,” the Arab said to them. “We go now to the last of the rooms.”

He explained the last room was for the baby. He showed the baby items and explained their use. The mademoiselle stood with the young man just inside the door. He motioned her to come forward.

“Here, mademoiselle, come put your hands on your knees like this.”

She shook her head. She did not want to do it.

“Come, mademoiselle, do as I say. It is the heat, you are overheated,” he explained.

She glanced at the young man and stepped into the center of the room. The American girl bent over with her hands on her knees. The Arab grinned at the young man. They had a complicity developing. He pushed her black top up on her back to expose as much skin from the shoulders to her waist. She pulled up. “Stay, stay, do not move,” he told her. “Stay, mademoiselle.” He placed his hands onto the tanned, smooth skin and felt her down slowly to the little hairs on her lower back. She tensed under his touch. He turned to wink at the young man but the young man had looked away.

“It is a great relief to touch here and here,” he said running his hands along her dress to the soft flesh at her hips.

“Now stand up.”

The Arab motioned for the young man to come and stand behind her. He had the young man hold the girl’s hands behind her. The Arab stood in front of the girl and jerked up the black top to expose her stomach. The mademoiselle reacted. Her top was half off.

“Sshh, very quiet, mademoiselle. Do not move. Hold her tight, m’sieur.” His hand smoothed slowly across her stomach, then ran up between her breasts. The girl shrieked and broke free from the hold of the young man.

“No, no, not finished mademoiselle. Not finished.” He clapped her stomach with his cupped hand three times and put his ear at her belly, listening.

“Try m’sieur, try to listen,” he motioned to the young man.

The monsieur hesitated, then came around and listened.

“You hear, of course, don’t you? You hear the air?”

The young man didn’t say anything.

“Tour stop,” the Arab said to him in English. He led the Americans out through the courtyard and to the doors. The Arab stood in the darkened corridor, smiling.

“Some dinar for your tour,” he said in English.

The young man put two dinar pieces in his hand. It was half of what he expected.

“M’sieur,” he said. “Mademoiselle,” he turned to her. “Four dinar. Four dinar is raisonable.”

She did not answer and would not look at him. The young man looked serious now, even angry. It was some joke maybe.

He held out his hand again for the monsieur and smiled. The young man put a two dinar coin in his hand and said something in English. The Arab opened one of the wooden doors and looking both ways led the American tourists out onto the bright street. The Arab locked the doors and went away quickly. The little Arab was gone.

The young man unfolded the yellow tourist map and looked around.

“Are you hungry, Liz?” he said finally.

She shook her head.

“What about a mint tea?”

“I want to go back to the hotel,” she told him. “I want chocolate,” she told him. “I want chocolate and I want a shower.”

“Well,” said the young man looking at their map, “We’ll need to find out where we are first.”

1.25.2010

Better Than Cocaine

1.23.2010

1.20.2010

Gathering Chestnuts

The bad weather came one day in the fall. A cold wind stripped the leaves from the trees and the leaves lay sodden on the streets in the rain. The cold and the rain made you sad, but with the bad weather we knew that chestnuts had been loosened from the chestnut trees throughout the city. Outside the metro stations men appeared selling the chestnuts they roasted on metal half-drums filled with hot coals and as you emerged from the underground there was the rich smoky smell of chestnuts cooking. The men pushed the drums in shopping carts and their fingers were black from handling the hot nuts and packing them into the paper cones they served them in. When the chestnut sellers appeared it was a signal that the chestnuts had begun to fall in the parks across Paris and that I could go gathering chestnuts of my own.

On rue de la Roquette near Nation I knew of a park with five, fine reliable trees that I had collected from before, and on this day I stuffed a plastic sack inside my pea coat and went to see if the chestnuts had fallen. It was cold and windy walking down rue Saint-Maur but I was warm walking and thinking of chestnuts, and I hoped to make a good collection and return to the apartment before the rains. I hoped for dark glossy chestnuts, flat on one side and round and full on the other, and a little soft when I pressed them so that I would know the nutmeat inside had matured and begun to pull away from the shell.

The benches at the park were empty in the late morning, the weather too harsh for even the hardiest old bench sitters. I stepped over the low railing onto the pelouse and began to pick up and feel of the chestnuts lying in the grass. All of them were a disappointment. They were solidly hard and would require hours of cooking and even then would be hard and bitter to eat. I considered letting them mature in the apartment, but then I badly wanted chestnuts today and knew too that Florence might disagree with a pile of chestnuts aging in the kitchen.

Then I recalled the chestnut piles I had once seen at Père Lachaise Cemetery. They had been rotten then but I wondered if I might find there a pile of freshly fallen chestnuts swept from off the graves and awaiting disposal.

The cemetery was not far and I entered through the main entrance on Boulevard de Menilmontant and up the cobblestone footpath I passed the empty grave that had held Rossini, and turning off I noticed beyond Chopin a new grave. I had not known of new graves at Père Lachaise and I saw it was for the dwarf jazz pianist Michel Petrucciani. I had not heard of his death and it surprised me. He had been a fine and very lyrical player and I stopped at the simple headstone and remembered him.

Walking north I looked in on Ingres and Daumier. Without a cemetery map it was easy to become lost on the footpaths among the headstones and monuments, but I was fortunate to remember certain graves to orient myself. At the intersection of Avenues Carette and Transversale I looked down the tree lined footpath where Oscar Wilde was buried. I remembered the monument of the winged naked messenger, the anatomical parts that had made and maintained the legend of Wilde chipped off it and stolen. I remembered the lipstick kisses his admirers planted on the headstone and how they turned to brown smudges. I did not remember chestnut trees there and it was not a grave I wished to go near.

It was along the Avenue des Peupliers that I spotted a large pile of chestnuts, and I sorted through them excitedly, feeling for the proper firmness and looking for nuts of a similar size so that they might cook uniformly on the stove. They all felt of the right maturity and had a dark, glossy shine that made me hungry to look at them. Mixed among them were horse chestnuts, which are inedible and, as they say, fit only for horses. They are often confused with the chestnut but come from an altogether different genus of trees and can be identified by the shell which is a duller brown and does not shine.

It was almost cheating to collect chestnuts this way from a pile, but later when we smelled them roasting it would matter very little how I had found them. I filled the sack and looked to mark the spot. I recognized at the intersection of the footpaths the tomb of Raymond Radiguet. Poor Radiguet had died too young but had written a very good book called Le Diable au Corps and it pleased me that he had been put near a fine chestnut tree. It was such a beautiful book that I did not understand how his second book was so poorly written and unreadable. I knew the rumor but did not want to believe that the first book had been written by the man who had corrupted him. I was glad knowing that man was not interred at the cemetery. I did not know where they put him but I hoped he was far away and difficult to find.

It had begun to rain and I made back for the main entrance under the plane trees and maples. There were so many good ones I had not stopped to visit. I thought of poor Apollinaire dying of the influenza and ordering the doctor to save him because there was so much left to write. And near him the statue of the lion tamer Jean Pezon, sitting atop Brutus, the lion who had eaten him. I thought too of the life-size bronze of Victor Noir, lying with his mouth open, and the young wives who had rubbed smooth a particular area of his anatomy for luck in pregnancy. There were all sorts of graves at Père Lachaise, some happy and some sad and even some that were tragic.

At home that night I showed Florence the fine chestnuts and told her where I had found them. She loved roasted chestnuts and that I had so many of such quality and that I had not needed to buy them. After dinner we worked together, scoring the flat side of the nuts with a knife so that moisture could release while cooking and the chestnuts did not explode. I cooked the nuts in the pan until the shell along the cut had curled to expose the tender nutmeat and they were ready to be eaten.

As we lay in bed eating from the plate of roasted chestnuts I explained that despite the high tariff I had decided to be buried at Père Lachaise.

“But the cemetery is full, mon cheri. And anyway you are not important enough to be buried there.”

“But I will be important enough one day,” I said, and felt certain of it. “And there is still room.” I told her of the midget Petrucciani who I had discovered there newly buried.

“Non, non,” she smiled. “He is there only because he takes up less room than a full grown man. There is no room for you. You are too big even now, mon cheri.”

We laughed and cracked open and finished the last chestnuts together. They were delicious chestnuts and we were both so happy to know now where to find them. In those days your happiness could be as simple and exciting as knowing where to find the chestnuts in the fall.

On rue de la Roquette near Nation I knew of a park with five, fine reliable trees that I had collected from before, and on this day I stuffed a plastic sack inside my pea coat and went to see if the chestnuts had fallen. It was cold and windy walking down rue Saint-Maur but I was warm walking and thinking of chestnuts, and I hoped to make a good collection and return to the apartment before the rains. I hoped for dark glossy chestnuts, flat on one side and round and full on the other, and a little soft when I pressed them so that I would know the nutmeat inside had matured and begun to pull away from the shell.

The benches at the park were empty in the late morning, the weather too harsh for even the hardiest old bench sitters. I stepped over the low railing onto the pelouse and began to pick up and feel of the chestnuts lying in the grass. All of them were a disappointment. They were solidly hard and would require hours of cooking and even then would be hard and bitter to eat. I considered letting them mature in the apartment, but then I badly wanted chestnuts today and knew too that Florence might disagree with a pile of chestnuts aging in the kitchen.

Then I recalled the chestnut piles I had once seen at Père Lachaise Cemetery. They had been rotten then but I wondered if I might find there a pile of freshly fallen chestnuts swept from off the graves and awaiting disposal.

The cemetery was not far and I entered through the main entrance on Boulevard de Menilmontant and up the cobblestone footpath I passed the empty grave that had held Rossini, and turning off I noticed beyond Chopin a new grave. I had not known of new graves at Père Lachaise and I saw it was for the dwarf jazz pianist Michel Petrucciani. I had not heard of his death and it surprised me. He had been a fine and very lyrical player and I stopped at the simple headstone and remembered him.

Walking north I looked in on Ingres and Daumier. Without a cemetery map it was easy to become lost on the footpaths among the headstones and monuments, but I was fortunate to remember certain graves to orient myself. At the intersection of Avenues Carette and Transversale I looked down the tree lined footpath where Oscar Wilde was buried. I remembered the monument of the winged naked messenger, the anatomical parts that had made and maintained the legend of Wilde chipped off it and stolen. I remembered the lipstick kisses his admirers planted on the headstone and how they turned to brown smudges. I did not remember chestnut trees there and it was not a grave I wished to go near.

It was along the Avenue des Peupliers that I spotted a large pile of chestnuts, and I sorted through them excitedly, feeling for the proper firmness and looking for nuts of a similar size so that they might cook uniformly on the stove. They all felt of the right maturity and had a dark, glossy shine that made me hungry to look at them. Mixed among them were horse chestnuts, which are inedible and, as they say, fit only for horses. They are often confused with the chestnut but come from an altogether different genus of trees and can be identified by the shell which is a duller brown and does not shine.

It was almost cheating to collect chestnuts this way from a pile, but later when we smelled them roasting it would matter very little how I had found them. I filled the sack and looked to mark the spot. I recognized at the intersection of the footpaths the tomb of Raymond Radiguet. Poor Radiguet had died too young but had written a very good book called Le Diable au Corps and it pleased me that he had been put near a fine chestnut tree. It was such a beautiful book that I did not understand how his second book was so poorly written and unreadable. I knew the rumor but did not want to believe that the first book had been written by the man who had corrupted him. I was glad knowing that man was not interred at the cemetery. I did not know where they put him but I hoped he was far away and difficult to find.

It had begun to rain and I made back for the main entrance under the plane trees and maples. There were so many good ones I had not stopped to visit. I thought of poor Apollinaire dying of the influenza and ordering the doctor to save him because there was so much left to write. And near him the statue of the lion tamer Jean Pezon, sitting atop Brutus, the lion who had eaten him. I thought too of the life-size bronze of Victor Noir, lying with his mouth open, and the young wives who had rubbed smooth a particular area of his anatomy for luck in pregnancy. There were all sorts of graves at Père Lachaise, some happy and some sad and even some that were tragic.

At home that night I showed Florence the fine chestnuts and told her where I had found them. She loved roasted chestnuts and that I had so many of such quality and that I had not needed to buy them. After dinner we worked together, scoring the flat side of the nuts with a knife so that moisture could release while cooking and the chestnuts did not explode. I cooked the nuts in the pan until the shell along the cut had curled to expose the tender nutmeat and they were ready to be eaten.

As we lay in bed eating from the plate of roasted chestnuts I explained that despite the high tariff I had decided to be buried at Père Lachaise.

“But the cemetery is full, mon cheri. And anyway you are not important enough to be buried there.”

“But I will be important enough one day,” I said, and felt certain of it. “And there is still room.” I told her of the midget Petrucciani who I had discovered there newly buried.

“Non, non,” she smiled. “He is there only because he takes up less room than a full grown man. There is no room for you. You are too big even now, mon cheri.”

We laughed and cracked open and finished the last chestnuts together. They were delicious chestnuts and we were both so happy to know now where to find them. In those days your happiness could be as simple and exciting as knowing where to find the chestnuts in the fall.

1.19.2010

Beta Gamma Sigma Honor Society

Dear Sir or Madam,

I today received, "courtesy" of your honor society, a bulk mail letter from Geico Insurance advertising its policies. Beta Gamma Sigma is noted on the bottom of the letter as having sold my personal information to Geico. As a longstanding member of your society (since sometime during my college years at XXXXX University), I think it is reasonable to ask for how much my information was sold. Furthermore, for this and any future sales of my personal information I would like to be compensated. My cut is 90% of the sale price for my name, address, and/or phone (should you somehow acquire it). I strike a hard bargain.

Should you refuse to pay me, I request immediate removal from your lowdown, weasily, huckster society. I'll make sure you regret it.

Sincerely yours,

I today received, "courtesy" of your honor society, a bulk mail letter from Geico Insurance advertising its policies. Beta Gamma Sigma is noted on the bottom of the letter as having sold my personal information to Geico. As a longstanding member of your society (since sometime during my college years at XXXXX University), I think it is reasonable to ask for how much my information was sold. Furthermore, for this and any future sales of my personal information I would like to be compensated. My cut is 90% of the sale price for my name, address, and/or phone (should you somehow acquire it). I strike a hard bargain.

Should you refuse to pay me, I request immediate removal from your lowdown, weasily, huckster society. I'll make sure you regret it.

Sincerely yours,

1.18.2010

1.14.2010

Becoming

1.12.2010

Words of Advice to Children and Grandchildren

I was born in Dahlshult Ocotober 22, 1821. My father was Peter Anderson and my mother was Christina Andersdotter. I was given early to my savior by being baptized and was named Lars Peter. I learned to read at an early age and received instruction in the Christian religion, particularly from my older half brothers and sisters (who had been pupils of Reverend Hof). Nevertheless, the sinful roots in my heart developed often into disobedience and selfishness and my parent’s warnings were received with ill will, although I early and often was aware of the reproaches of my conscience. I learned writing and arithmetic and received a thorough instruction in the Christian religion.

When I, at an age of 15 years, was confirmed, the Reverend C. F. Nilson stated that I had a good knowledge of the Christian religion. This flattered me, although I knew that the condition of my conscience was not as it ought to have been at that time, although from the thorough teaching and urging I received during the preparation of my confirmation, I had often emotional feelings and made some weak resolution to improve, but because of the less suitable companionship I was seeking and found outside my home, I became a lighthearted, and for religion, a thoughtless young man.

I lost my father in the year 1843 and the following year I married Miss Lovisa Nilson from Brannesbacka, daughter of a sea captain, N. Nilson. These years of my life were of special importance. My father was ill for a long time and during that time had visits of an earnest and zealous clergyman from a nearby parish. My future wife took sick the same year form typhoid fever and was visited by the same honest teacher and became thereby taken by the spirit of God, so that she on her side also took a solemn step to renounce sin and worldliness. This, together with the sorrow over my beloved father’s death, was for me also a strong “Father drawing towards Son” that I did also seriously make up my mind to improve.

After my parents-in-law had celebrated our wedding and my wife had moved to our home, we together often visited and listened to the divine services by the previous mentioned clergyman at the nearby parish (he also visited us) and he urged and encouraged us to seek in all seriousness God and His righteousness. The years pass. Our marriage was blessed with 8 children, 5 boys and 3 girls. One girl, the seventh child, after living only three weeks, moved into her heavenly Father’s home. God blessed also our worldly goods so that I feared that I would get my “share” in this life only.

For many years we were both in good health. I received many municipal appointments and responsibilities and because of that I allowed my thoughts and mind to be divided into worldly matters. My decision to improve I renewed daily but I noticed that sin followed me and realizing my sinfulness, my weakness, my great plight, I still did not have the courage to freely throw myself on His mercy or console me of my sins forgiveness, because (as I thought) I would immediately fall again and “without sanction nobody can see God”. I did not consider that Christ is given to us by God for wisdom, for justice, for confirm and delivery. Oh! If I had come to him who said: “If you believe you shall see God’s glory.” Now instead I have been torn between fear and hope, between love for the world and abhorrence for its folly. I fought against sin but without success, and I often called out “I poor layman, who shall free me from this wasted, sinful body.”

But God through his wealth of goodness, wants to tempt us to salvation and he sent me a cross to carry. Through a body affliction, my health became so weakened that I was unable to perform any hard work, and I realize now that this was to draw me to the Lord. Oh! That now I had let me to be drawn, I can still feel my unworthiness, my weakness. Oh! I am the most miserable, but whom shall go to but to Jesus, my sin’s redeemer, and who has said “Whom so ever comes to me, he shall not be thrown out.”

And now I am standing at the side of my grave with this prayer: “Lord, think not of the sins of my youth, my manhood errors and my transgressions, but think of me for thine mercies and thine goodness sake.” God have mercy over me, the sinner. And now my beloved wife: “Thank you for your true love, you have been God’s messenger and instrument to drag me away from the vanity of the world, a reason an encouragement for a more serious intent of seeking the salvation of my soul. I hope now that the suffering from your separation shall be softened because “soon we shall meet again in the swelling of peace.”

And now my beloved children: I will die and may God bless you. Believe in him and his teachings. I must confess that I may have neglected much in your bringing up; but if you have opportunity to absorb knowledge and reason to practice true Christianity, do not forget the teachings and examples you received in your home. Your childhood and youth may have already passed, so you need seriously to pray: “Think not of the sins and transgressions of my youth, but think of me for thine mercy and thine goodness sake, O Lord.”

And so one word to you my beloved grandchildren. Think of your creator in your youth before evil days arrive and the coming years of which it might be said they are not to my liking. Realize that to believe in God is useful in all situations and promises a happy life in this world as well as in the world beyond. Do not love the world or worldly things such as sensuousness, greed and self-esteem, because this world’s beings perish. Do not let yourself be misled; wicked talk destroys good habits; avoid drinking; gambling and dancing; do not take part in evil jests as true Christians do not practice those things because God shall bring to light all doings before the great judge, even those things that are secret.

--Lars Peter Peterson Dahlshult

(translation from the Swedish)

When I, at an age of 15 years, was confirmed, the Reverend C. F. Nilson stated that I had a good knowledge of the Christian religion. This flattered me, although I knew that the condition of my conscience was not as it ought to have been at that time, although from the thorough teaching and urging I received during the preparation of my confirmation, I had often emotional feelings and made some weak resolution to improve, but because of the less suitable companionship I was seeking and found outside my home, I became a lighthearted, and for religion, a thoughtless young man.

I lost my father in the year 1843 and the following year I married Miss Lovisa Nilson from Brannesbacka, daughter of a sea captain, N. Nilson. These years of my life were of special importance. My father was ill for a long time and during that time had visits of an earnest and zealous clergyman from a nearby parish. My future wife took sick the same year form typhoid fever and was visited by the same honest teacher and became thereby taken by the spirit of God, so that she on her side also took a solemn step to renounce sin and worldliness. This, together with the sorrow over my beloved father’s death, was for me also a strong “Father drawing towards Son” that I did also seriously make up my mind to improve.

After my parents-in-law had celebrated our wedding and my wife had moved to our home, we together often visited and listened to the divine services by the previous mentioned clergyman at the nearby parish (he also visited us) and he urged and encouraged us to seek in all seriousness God and His righteousness. The years pass. Our marriage was blessed with 8 children, 5 boys and 3 girls. One girl, the seventh child, after living only three weeks, moved into her heavenly Father’s home. God blessed also our worldly goods so that I feared that I would get my “share” in this life only.

For many years we were both in good health. I received many municipal appointments and responsibilities and because of that I allowed my thoughts and mind to be divided into worldly matters. My decision to improve I renewed daily but I noticed that sin followed me and realizing my sinfulness, my weakness, my great plight, I still did not have the courage to freely throw myself on His mercy or console me of my sins forgiveness, because (as I thought) I would immediately fall again and “without sanction nobody can see God”. I did not consider that Christ is given to us by God for wisdom, for justice, for confirm and delivery. Oh! If I had come to him who said: “If you believe you shall see God’s glory.” Now instead I have been torn between fear and hope, between love for the world and abhorrence for its folly. I fought against sin but without success, and I often called out “I poor layman, who shall free me from this wasted, sinful body.”

But God through his wealth of goodness, wants to tempt us to salvation and he sent me a cross to carry. Through a body affliction, my health became so weakened that I was unable to perform any hard work, and I realize now that this was to draw me to the Lord. Oh! That now I had let me to be drawn, I can still feel my unworthiness, my weakness. Oh! I am the most miserable, but whom shall go to but to Jesus, my sin’s redeemer, and who has said “Whom so ever comes to me, he shall not be thrown out.”

And now I am standing at the side of my grave with this prayer: “Lord, think not of the sins of my youth, my manhood errors and my transgressions, but think of me for thine mercies and thine goodness sake.” God have mercy over me, the sinner. And now my beloved wife: “Thank you for your true love, you have been God’s messenger and instrument to drag me away from the vanity of the world, a reason an encouragement for a more serious intent of seeking the salvation of my soul. I hope now that the suffering from your separation shall be softened because “soon we shall meet again in the swelling of peace.”

And now my beloved children: I will die and may God bless you. Believe in him and his teachings. I must confess that I may have neglected much in your bringing up; but if you have opportunity to absorb knowledge and reason to practice true Christianity, do not forget the teachings and examples you received in your home. Your childhood and youth may have already passed, so you need seriously to pray: “Think not of the sins and transgressions of my youth, but think of me for thine mercy and thine goodness sake, O Lord.”

And so one word to you my beloved grandchildren. Think of your creator in your youth before evil days arrive and the coming years of which it might be said they are not to my liking. Realize that to believe in God is useful in all situations and promises a happy life in this world as well as in the world beyond. Do not love the world or worldly things such as sensuousness, greed and self-esteem, because this world’s beings perish. Do not let yourself be misled; wicked talk destroys good habits; avoid drinking; gambling and dancing; do not take part in evil jests as true Christians do not practice those things because God shall bring to light all doings before the great judge, even those things that are secret.

--Lars Peter Peterson Dahlshult

(translation from the Swedish)

1.11.2010

$157 per week + $25 federal stimulus

November 12, 2009

November 12, 2009Attn: xxxxxxxxxxxx

Re: Freight team transition to daytime

Upon further consideration I have decided to take the unemployment insurance option in lieu of making the transition to daytime associate. The job I was hired to do in April 2009 was a simple one: move freight from receiving to the shelves during the night in the garden department. Then and now this is the position I wanted--one which does not include any customer interaction, extensive product knowledge, sales, or working during the daytime. Thus, I shall be going on unemployment until I am able to find a suitable replacement overnight freight position.

Best of luck to you and the rest of the team at #19xx in meeting your sales goals for 2009, and thanks again for accommodating my request for unpaid vacation during the week of November 16-20. Please note that as a result of this unpaid vacation occurring in the week prior to the freight team transition, my last paid day of work will be the 14th of November, though my last official day of employment at xxxxxxxxxx will be the 20th.

Best Regards,

1.07.2010

Part One

Jim scanned the ice for his tip-ups. The fishing traps he had set made three orange marks against the snow. None of the orange flags were up and he looked away. A fish would not strike a tip-up if you were watching it. The chances were better when you did something else. It was better to watch the geese or the crows or kick around a piece of ice you chiseled from a hole. But it was too cold for birds today and he didn’t want to move. Still he had to do something. He had not had a flag yet. It was hard fishing alone in the very cold.

Jim turned upwind, the ice smooth out to the gray woods and up through the channel the big lake stretching out far and white. He was the only fisherman on the lakes. The wind stung his face and he turned away. Anyway it was better without others on the ice. They watched you fishing a hole and there was too much pressure. There wasn’t anything wrong with fishing alone. You fished where you wanted and how you wanted.

Far left an orange flag flung up swinging. Jim’s heart went pounding. His first tip-up. In the wind he had even heard the tiny metallic click of the flag releasing from the post. Jim started towards the flag, careful so his boots on the ice would not spook the fish. Halfway he saw the metal post that had tipped the flag spinning wildly. Line was pulling fast off the spool underwater. It must be a bass. He had put that tip-up in along the weed bar. He was running with the minnow for the weeds in the shallow water.

Jim knelt down at the hole before the tip-up, the post spinning furiously on the wooden base across the hole. The line slowed going out and Jim pulled off his mittens. The line went out very slow and stopped. Jim slipped his hands into the freezing water, and holding the line in place below the spool drew out the tip-up and laid it on the ice beside the hole. Now the hole was free of the tip-up apparatus. He began to carefully bring in the slack line between him and the fish. He took line in slowly until he felt the tension. There was something heavy and alive on the other end. He felt the line now taut between him and the fish. There was a tiny pull. He let the line go some. He brought some in. There again was the tension. Jim set himself to strike against the fish, but just then the line went slack in his hands. He had spit the minnow. It wasn’t over though. A hungry one like that was sure to come back.

Jim balanced the wood base of the tip-up at the edge of the hole so the line spool was back in the water. In the cold the wet line had frozen quickly on the spool. In the water the line would unfreeze and when the big fish returned there would be line to go out. He sat back on his boots and jammed his hands, raw and cramped from the icy water, inside his snowsuit. His hands hurt but it might be just a minute until the big fish returned. He had to be ready.

He watched the line down into the dark water. The minnow was down there somewhere, laying in the weeds, stunned, maybe part eaten but still alive, the big fish gone away. He understood why they spit the minnow, it was because they felt the hook, but why they returned Jim did not understand. They somehow always remembered where they left it. It didn’t matter how deep and mixed up in the weeds the minnow was, they remembered. He just had to wait. He just had to be patient and the big fish would come back.

The line fidgeted and jerked and went out hard off the spool. It was started again. But the line slowed and stopped. This sure was an indecisive one, Jim thought. He had to be a young one. I wish he’d just make up his mind what he wanted.

The line started out again and very slowly, and Jim saw it was time and fast reached into the water for the line and feeling immediately the un-giving tension set hard the hook with a short tug towards his body; then up on his feet hand-over-hand bringing in line feeling the weight and drag of something heavy and fighting and bursting out the hole with weeds and muck was the young bass. It came out flopping angry on the ice beside the hole. Jim pulled the weeds off him. He was a beauty of a bass. Jim put his hands back inside his snowjacket to warm them as he admired the flopping bass. He was young but he was big. He was big enough to keep.

Jim folded back the dorsal fin to get a hold and take the hook out. The largemouth was too thick in the belly to hold well and the mucus was already making him slippery. Jim’s hands were so raw and cold they hardly worked. He got a good hold finally, and with his small pliers worked the barb of the hook out the jaw with a pop. He tossed the fish onto the ice away from the hole and rubbed the mucus off his hands on his snowpants. That bass would freeze up quick in this cold.

Jim stuffed his hands inside his suit. They were frozen from the cold air and water. They hurt so much. The wind blew hard and he felt it on his back through the snowsuit. The tip-up lay beside the hole, the line frozen and tangled across the ice. He did not want to take his hands out and untangle the line and re-set the tip-up. Jim felt a reaction against reaching into the icy minnow bucket water and holding the squirming minnow, his wet hands burning in the cold, hooking it and re-setting the tip-up with a fresh minnow.

Near the hole the bass was not moving, already frozen solid. Now I’ve got one, Jim thought. One was enough, he guessed. He didn’t really need to catch another. He didn’t have to fish any longer if he didn’t want to. He could go where it was warm. At the house his grandfather would have a big fire going. All the times after fishing they went there. Laying on his back he would put his wool-socked feet up against the hot glass doors of the fireplace. When his toes and feet were hot he would stand with his back at the fire, his hands warming on the hot chimney bricks. Sometimes Grandpa Olaf even made them glögg to warm them from the inside out. He didn’t have to be out here in the cold any longer. It wasn’t necessary.

Jim picked up the spent tip-up and started to wind the line onto the spool, untangling line with his other hand. He would take his gear to the cabin and then go down to the house to see his grandfather. Jim broke the tip-up down, folding the metal post flat with the wooden base, then pushed the hook into the wood.

Jim walked to the next tip-up, tipped the flag, and wound line until the minnow lifted from the water. He pulled the minnow off the hook, dropped it on the ice and folded up the tip-up. Jim went to the last tip-up and brought it in. He put the frozen bass and the tip-ups in the bucket and with his chisel and his ice scoop he picked up the covered pail containing the minnows and started towards the shore. He was going in.

Jim turned upwind, the ice smooth out to the gray woods and up through the channel the big lake stretching out far and white. He was the only fisherman on the lakes. The wind stung his face and he turned away. Anyway it was better without others on the ice. They watched you fishing a hole and there was too much pressure. There wasn’t anything wrong with fishing alone. You fished where you wanted and how you wanted.

Far left an orange flag flung up swinging. Jim’s heart went pounding. His first tip-up. In the wind he had even heard the tiny metallic click of the flag releasing from the post. Jim started towards the flag, careful so his boots on the ice would not spook the fish. Halfway he saw the metal post that had tipped the flag spinning wildly. Line was pulling fast off the spool underwater. It must be a bass. He had put that tip-up in along the weed bar. He was running with the minnow for the weeds in the shallow water.

Jim knelt down at the hole before the tip-up, the post spinning furiously on the wooden base across the hole. The line slowed going out and Jim pulled off his mittens. The line went out very slow and stopped. Jim slipped his hands into the freezing water, and holding the line in place below the spool drew out the tip-up and laid it on the ice beside the hole. Now the hole was free of the tip-up apparatus. He began to carefully bring in the slack line between him and the fish. He took line in slowly until he felt the tension. There was something heavy and alive on the other end. He felt the line now taut between him and the fish. There was a tiny pull. He let the line go some. He brought some in. There again was the tension. Jim set himself to strike against the fish, but just then the line went slack in his hands. He had spit the minnow. It wasn’t over though. A hungry one like that was sure to come back.

Jim balanced the wood base of the tip-up at the edge of the hole so the line spool was back in the water. In the cold the wet line had frozen quickly on the spool. In the water the line would unfreeze and when the big fish returned there would be line to go out. He sat back on his boots and jammed his hands, raw and cramped from the icy water, inside his snowsuit. His hands hurt but it might be just a minute until the big fish returned. He had to be ready.

He watched the line down into the dark water. The minnow was down there somewhere, laying in the weeds, stunned, maybe part eaten but still alive, the big fish gone away. He understood why they spit the minnow, it was because they felt the hook, but why they returned Jim did not understand. They somehow always remembered where they left it. It didn’t matter how deep and mixed up in the weeds the minnow was, they remembered. He just had to wait. He just had to be patient and the big fish would come back.

The line fidgeted and jerked and went out hard off the spool. It was started again. But the line slowed and stopped. This sure was an indecisive one, Jim thought. He had to be a young one. I wish he’d just make up his mind what he wanted.

The line started out again and very slowly, and Jim saw it was time and fast reached into the water for the line and feeling immediately the un-giving tension set hard the hook with a short tug towards his body; then up on his feet hand-over-hand bringing in line feeling the weight and drag of something heavy and fighting and bursting out the hole with weeds and muck was the young bass. It came out flopping angry on the ice beside the hole. Jim pulled the weeds off him. He was a beauty of a bass. Jim put his hands back inside his snowjacket to warm them as he admired the flopping bass. He was young but he was big. He was big enough to keep.

Jim folded back the dorsal fin to get a hold and take the hook out. The largemouth was too thick in the belly to hold well and the mucus was already making him slippery. Jim’s hands were so raw and cold they hardly worked. He got a good hold finally, and with his small pliers worked the barb of the hook out the jaw with a pop. He tossed the fish onto the ice away from the hole and rubbed the mucus off his hands on his snowpants. That bass would freeze up quick in this cold.

Jim stuffed his hands inside his suit. They were frozen from the cold air and water. They hurt so much. The wind blew hard and he felt it on his back through the snowsuit. The tip-up lay beside the hole, the line frozen and tangled across the ice. He did not want to take his hands out and untangle the line and re-set the tip-up. Jim felt a reaction against reaching into the icy minnow bucket water and holding the squirming minnow, his wet hands burning in the cold, hooking it and re-setting the tip-up with a fresh minnow.

Near the hole the bass was not moving, already frozen solid. Now I’ve got one, Jim thought. One was enough, he guessed. He didn’t really need to catch another. He didn’t have to fish any longer if he didn’t want to. He could go where it was warm. At the house his grandfather would have a big fire going. All the times after fishing they went there. Laying on his back he would put his wool-socked feet up against the hot glass doors of the fireplace. When his toes and feet were hot he would stand with his back at the fire, his hands warming on the hot chimney bricks. Sometimes Grandpa Olaf even made them glögg to warm them from the inside out. He didn’t have to be out here in the cold any longer. It wasn’t necessary.

Jim picked up the spent tip-up and started to wind the line onto the spool, untangling line with his other hand. He would take his gear to the cabin and then go down to the house to see his grandfather. Jim broke the tip-up down, folding the metal post flat with the wooden base, then pushed the hook into the wood.

Jim walked to the next tip-up, tipped the flag, and wound line until the minnow lifted from the water. He pulled the minnow off the hook, dropped it on the ice and folded up the tip-up. Jim went to the last tip-up and brought it in. He put the frozen bass and the tip-ups in the bucket and with his chisel and his ice scoop he picked up the covered pail containing the minnows and started towards the shore. He was going in.

1.06.2010

1.03.2010

1.02.2010

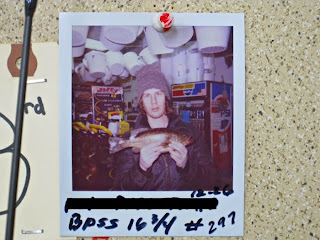

Bait Shop

The old guy at Malchow's says, "You want me to measure that?"

"That's what I brought it for," I says.

I took it out of the newspaper for him and he laid it on the blood stained ruler.

"Its not 17," he says.

"Ok. But it gets me on the board."

"You want me to take a picture?" he says.

"Yeah."

"Hold it higher. Hold it with two hands."

He takes the picture.

"You want it on the board," he says.

"Yeah, I want it on the board. That's why you took the picture, isn't it?"

"Its not going to win," he says. "You won't win that rifle. 21 is gonna win."

"Then give me the picture," I says.

"No."

"It doesn't matter then, so give it to me."

"No," he says. He pins up the picture.

"They catch them on Round Lake," he says. "That's where you need to go."

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)